by Kamau Muiga @kamaumuiga

Tuesday, September 10, 2019

An impassioned storm was recently ignited on social media by reports that two chiefs had been arrested in Wajir county amidst allegations of inflating population figures in the national census, a rather interesting departure from the typical indifference that generally greets reports of wrongdoing in the conduct of public affairs.

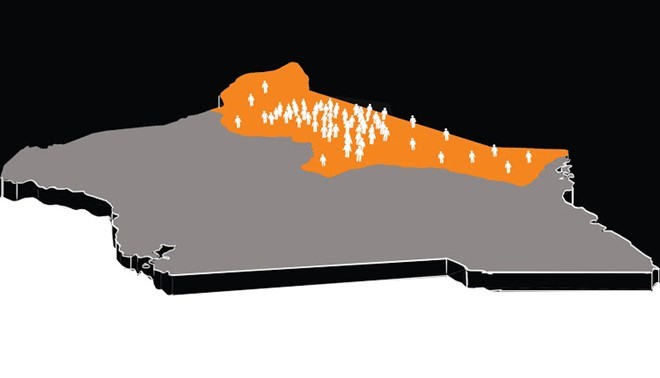

Population figures in the former Northeastern Province, which most Somali Kenyans call home, have always been a hotly contested issue every time the counting exercise is around the corner. Census results from Mandera, Wajir and Garissa were cancelled and revised downwards by the Planning ministry in 2009, sparking a legal battle between the government and political representatives from the region.

In February, Moses Kuria, the eccentric MP for Gatundu South, enraged sections of the Somali community when he warned in a Facebook post about foreign nationals crossing the border "to beef up the numbers of some communities". He added crudely that this time the government would be "using biometric technology, not improvised explosive devices" to conduct the census.

'Tyranny: Somalis race to join Big Four' was the headline splashed across the front page of a Saturday Standard edition in March 2018, evoking the famous tyranny of numbers mantra first popularised by Mutahi Ngunyi to describe Kenya's heavily ethnicised political scene. On Kenyan streets nowadays, in bars, social gatherings and dinner tables, there are endless whispers about Somalis "taking over" the country.

The distinguished American scholar Noam Chomsky once described his country's white population as a group continuously terrified that an empowered black population would turn around and take revenge for their historical oppression. The same psychosis plagued the white minority in apartheid South Africa who feared that black people, once in power, would treat white people just as badly as they had treated them.

Ever since the Union Jack descended from Kenyan flagpoles in 1963, the Kenyan cake has been eaten in an extremely inequitable fashion. The tribe of the president has been a reliable indicator of the general flow of resources, patronage and jobs in the public sector. In 1971, notes the historian Daniel Branch in his book Kenya: Between Hope and Despair, an entire half of the 222 top earners in the civil service were Kikuyu. The same ranks filled up disproportionately with people of Kalenjin ethnicity in the 1980s as the new tribe moved into State House, a vicious tribal game that continues to this day.

This gross unfairness was one of the key factors behind the stark inequalities that crystallised on the Kenyan scene as the decades went along. By the turn of the millennium, according to a 2004 report on inequality in Kenya by the Society for International Development, people living in Central Province were six times more likely to have a job than people living in Northeastern Province; 12 times more likely to have access to piped water; six times more likely to have access to electricity and five times more likely to be enrolled in primary school.

For tribes that have been heavily represented in power since Independence, the tribal game has paid off handsomely at the expense of those who have not been on the right side of the tyranny of numbers. The visceral fear of Somali population growth currently spreading on the Kenyan social landscape is the dread of a guilty party afraid of the tables being turned, afraid that once Somali Kenyans are numerous enough to control state resources in Kenya, they will treat the rest of us just as we have treated them since Independence. The guilty, indeed, are always afraid.

In a just society where tribe does not matter at all, where a person from a tiny tribe is just as likely to be healthy, well fed, educated, employed and secure as a person from a large tribe, where the tribe of the president says nothing about the flow of resources and opportunities, there would be nothing to fear about the population growth of any particular community. But we have thoroughly failed to create such a society, and so we must live with the consequences of our actions.

Lecturer and political analyst